cloud.microsoft Unified Namespace

Yesterday Microsoft announced that all Microsoft 365 app URL’s will migrate over time to *.cloud.microsoft, and I cannot stress how happy this makes me. As the footprint of Microsoft cloud services has grown over time, so, too has the number of wildly disparate namespaces that we have to manage, both in our endpoint and network configurations.

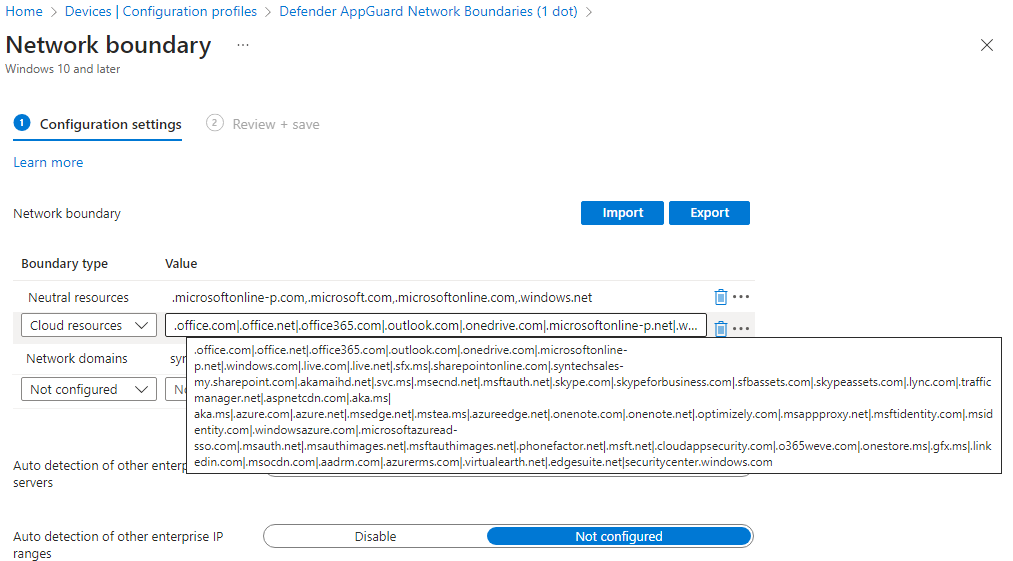

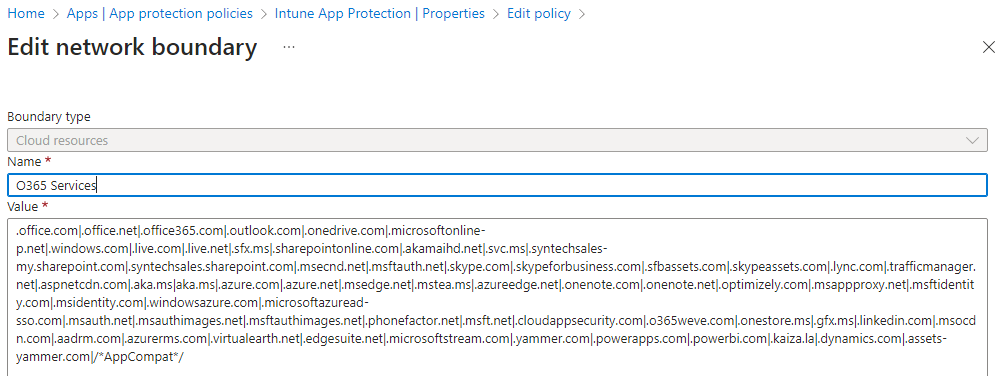

There are currently no fewer than 50 internet domains that have to be available for your users to access cloud services (and many, many more optional), as anybody who’s ever configured Defender AppGuard or Windows Information Protection network boundaries can tell you from experience:

Soon, though, both of these bulky entries can be reduced to just “.cloud.microsoft”, which will not just capture all of the current services, but will also scale to future services, so you can set fire-and-forget entries in both interfaces, along with network traffic-monitoring devices.

Users trying to access their favorite cloud apps will then point to outlook.cloud.microsoft for email, onedrive.cloud.microsoft for OneDrive, teams.cloud.microsoft for Teams, and so on in shockingly logical order.

While all of this is a welcome change, it’s not happening overnight, so for now you can plan to just add “.cloud.microsoft” to existing access rules.

But the implications of this change exceed just security configurations, as Microsoft just recently—in late 2022—made it possible to change your primary SharePoint Online URL, a capability that had been requested for over a decade and was so significant it saw many customers migrate their entire cloud infrastructures to new tenants. The capability was not without its limitations, however, as the caveats in the how-to documentation were as lengthy as many whole deployment guides. With the entirety of the cloud app infrastructure moving to .cloud.microsoft, this means eventually you will have to go through that SharePoint URL migration process, though hopefully the process will have been greatly simplified by the time a migration becomes mandatory.

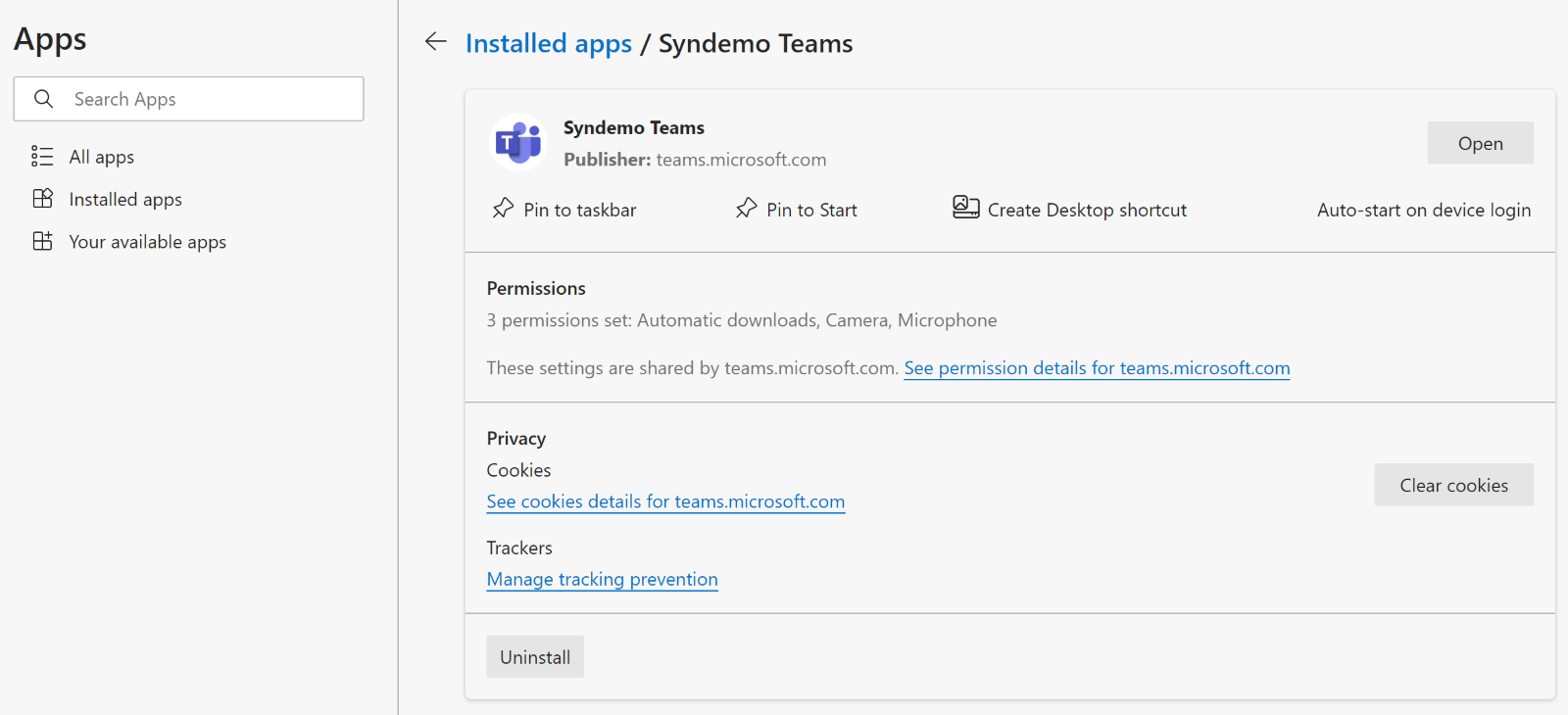

There’s also future implication around training. It’s all well & good for Microsoft to change URL’s that users don’t see, but eventually they do have to browse to a URL. While the service-specific URL’s announced in this change are super easy to remember, they will have to be communicated to users, and web-app users will be the hardest hit. Start planning now to address frontline workers and those who’ve grown accustomed to starting their day at locations like https://portal.office.com (which itself currently redirects to https://www.microsoft365.com), or have saved links in browsers or pinned to desktops for specific web apps. Microsoft Edge, in particular, has supported installing websites as apps on Windows desktops, and it’s the primary method users have adopted to keep Teams active in separate tenants without switching in the desktop app:

These apps may have to be re-created at some point, as may pinned apps within Teams channels themselves, particularly if they’ve been pinned as websites.

The last time I can recall a URL change of this magnitude was back in 2011, when Microsoft changed the AutoDiscover domain for Exchange Online mailboxes. We masked that change for users by manipulating DNS resolution, and the user impact was a fraction of a percent of our install-base.

In general, I do not see this change as being tremendously disruptive if it’s managed correctly, so just like any service-level change, it’s a great idea to start inventorying touch-points & potential impacts now to be aware of risk and ahead of changes.

Comments